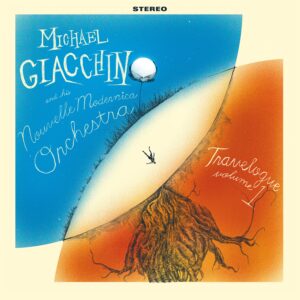

Academy Award-winning composer Michael Giacchino discusses his new album, Travelogue Volume 1, breaks down his writing process and reveals his favorite composing project.

Michael Giacchino has composed scores for some of the most popular and acclaimed film projects in recent history, including The Incredibles, War for the Planet of the Apes, Ratatouille, Star Trek, Jurassic World, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Spider-Man: Far from Home and Coco. Giacchino’s 2009 score for the Pixar’s Up earned him an Oscar, a Golden Globe, the BAFTA, the Broadcast Film Critics’ Choice Award and two GRAMMY Awards. Giacchino also took home an Emmy for his work on the pilot episode of J.J. Abram’s series LOST and a GRAMMY for the soundtrack for Ratatouille. His work can currently be heard in the Kevin Costner film Let Him Go, and will soon be heard in Matt Reeves’ The Batman.

Now, after a nearly three decade- long career, Giacchino has released his first non-soundtrack album, Travelogue Volume 1, a concept album that chronicles an alien’s search for a better life here on Earth, though discovering that our problems may be no better than those on their homeworld. We had the opportunity to talk with Mr. Giacchino about the new project.

This is your first non-soundtrack album in your twenty-six-year career. Why now? Was it a result of production being shut down due to the pandemic?

Well, it certainly allowed me the time to do it. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for a very long time, but there was just never time because all those movies would just back up against each other. That just kept going on for years. I love all those movies I’ve worked on. I love working on Star Trek and Star Wars and all the Marvel projects and Pixar films, but there’s also something about needing some time for yourself to work on your own thing.

As an artist, you are driven to do things, and I just kind of miss those days when I was able to just sit down and do what I wanted to do. So, we all found ourselves at this place where we weren’t allowed to go anywhere, and I thought, “Well, maybe this is the time to sit down and refocus and do some things for me. The album was the first thing on my list. I’ve been wanting to do make a record for so long like the records I grew up listening to like Arthur Lyman and Martin Denny and Les Baxter. They were writing this sort of fantasy music. They took you away somewhere. Sometimes they would take you to somewhere like the tropics, but it wasn’t necessarily tied to anything particular place. It was more of someone’s imagination; an idea of what that place might hold and the promise of an adventure.

It’s interesting that you say that because your work has primarily been used to support a narrative, and now here in your own work, you’ve created your own narrative. What was the decision behind that?

I think it mostly came from my love of old radio dramas. I especially love science fiction radio dramas. I’ve always listened to them. When I’m not working, I’m not generally not listening to music. I would say most of the time I’m listening to those old radio shows. One, in particular, was called X Minus One and it was, it was a great show and had great writers on it. It was sort of like Twilight Zone and Star Trek in the way that it dealt with its storytelling, so I thought it’d be fun to write a show like that. I also kept thinking that be fun to do one of those old lounge albums as well. And then I thought, “Oh, why not just push it all together?”

I think the thing that forced the story for this particular album was everything going on in the world. Between, the pandemic, the political unrest going on and the mess that is our world at the moment. I was thinking, “What if there’s another world like ours that is suffering under the same sort of ailments it’s got racism and pollution and political unrest?” And what if someone from that planet came across Voyager that we had sent out in the seventies and thought, “Well, maybe this place is better. This sounds like a wonderful place. Let’s go there and escape this mess that we’re in at the moment.”

So, they do that. They go. They come across Earth. At first, they think it’s great, but after a bit of time here, they realize that it’s not that much better than where they came from. In fact, in some ways, it’s worse. It forces an existential question of “What do I do? Should I run from the problems that are engulfing my home, or should I stay and try to face those problems and make the world better for whoever comes after me?” So that’s what the album is asking, in a weird science fiction way, which is what I always love about great science fiction. It takes on social issues of the day and turns them on their head.

You mentioned your influences, and the album has a very 1960s, Polynesian, Lex Baxter-like lounge music sound, but it also has a hint of a neo-futuristic science fiction vibe with the use of the theremin, similar to your Space Mountain theme. Throughout your career, you have been pretty diverse in your writing, more so than most composers. Can you talk about the writing process as far as what works together when you’re combining different styles of music?

You know, it’s weird. It’s a bit like cooking. I always think about Ratatouille whenever I’m doing these things, because there was a point where [director] Brad Bird said, “You know, this score, it should feel like you just went into the kitchen and you’re like, ‘All right, I gotta make dinner. What do I have around what’s around me? All right. I have a little bit of this, and I have a little bit of that and some of this, and you throw it all together and you create something new.’” In the creation of this album, I thought a lot about what he said because this is really what the album is, and it’s really taking all of those influences, all those things I grew up with, and throwing them into the mix and seeing what comes out.

That’s, what’s great about art. Art influences art, so all of that art I grew up with and lived with and loved, it’s sort of now influencing this newer thing, which, when you listen to it, you’re like, “Yeah, I hear echoes of this and echoes of that,” but it’s all still its own thing. So, the process is really just making myself smile, I guess. When I’m writing something, I think, “Oh yeah, that feels that feels right,’ or hitting a tone that feels emotional or reflective or thoughtful, whatever I’m feeling at the moment.

It’s very similar to scoring films in a way because what I’m trying to do is tap into the emotions that I’m feeling when I’m watching the movie, and this was all about tapping into the emotions that I was feeling in terms of the story I was trying to tell and, and, and write music that really spoke to that. So, the process is a bit nebulous. It’s, it’s not an easy step one, two, three, four thing. It’s more like going into a dark cave with a faulty flashlight and hoping that you can find your way through to the other side.

You mentioned the emotion, and with a lot of your work you’ve been able to really evoke emotion, LOST, Up and Inside Out in particular, and the last song on this album, Remembrance, is similarly emotional. Can you talk about that song?

Yeah, that was the very last one that I wrote. It was, it was interesting because I kept thinking about how I wanted to end this whole story, and there was a point where that song didn’t even exist. When I was finished, I thought, “All right, the album’s done. That’s it,” and then I was listening to the album and I was reflecting on that whole process of making it and what it meant to me. I thought, “You know, I have one more idea,” because I just wanted to tap into that feeling of finishing something and reflecting on it. That’s what that piece was, was about sort of like I imagined that being years after, uh, the main character’s journey that a reflection upon that time where they did go out in on this adventure did try to find something better only to realize that what’s better is at home.

I imagine that as a real embodiment of that thoughtful process of the journey that they went on in their past, and in the real world it’s me reflecting on a lot of things during this time; work and friends and the journey it takes to create something. It’s a bit of an emotional letdown when you finish a project, and this was one of the ones that I could actually add something to it to talk about that aspect. Normally that’s something reserved for your talk with your friends later at the premiere or whatever. You don’t actually get to create something that reflects that a loss of something like that those creative friendships that you make when you’re working on movies and things like that.

You produced this during the quarantine, so, what was the recording process like? Obviously, you couldn’t gather your orchestra together.

No. My normal way of doing it is having everyone in the same room at the same time and we just work it out together, but that couldn’t happen here obviously. So, I was thinking about it and I thought we could bring people here to record it, but that didn’t seem safe. Then I got an email from Abe Laboriel Jr., who is an amazing drummer and the son of Abe Laboriel, who has been my bass player on everything that I’ve done and one of the greatest bass players in the world. Junior is Paul McCartney’s drummer, but with everything shut down, he just emailed me and said, “Hey, you know, I’m around. If you’ve got anything you want to do, I’m around to play.” I think people were looking for things to do, to keep, take their minds off of everything and to keep themselves creative. So, I pitched him this idea. I said, “Look, I just started writing this thing, and I hadn’t even honestly thought about how I was going to record it yet, but. If you’re willing, why don’t I send you some tracks, and we could go from there?” He said, “Yeah, send them over”

I sent him demos and charts of what I wanted, and he would then record everything and send me back the tracks and I thought, “Oh, this could work.” So, I called up all the other musicians that I normally work with and said, “Hey, I’m doing this thing, do you want to do it?” It was great waking up and seeing that a file had been sent over. It was like getting a gift every morning. “Oh, the piano is here, or the harp is here.” It was just such a joy to still be able to work with everyone during this time. It was very different from what we normally do. And yet when you listen to it, you can’t tell, which I think is the result of us playing together for twenty years. We know each other so well and they know what I like. They added things that I never even would have thought of. We’ve talked about another album, which, we would have recorded altogether, but now I’m thinking that maybe we won’t because it worked out surprisingly well.

Before I let you go, my wife and I recently re-watched LOST with our sixteen-year-old daughter and nine-year-old son, and they loved it as much as we did. A composer is rarely that integral to the success of a series. Can you talk a bit about working on the show?

Well, first of all, thank you, that’s awesome. I love that. People often ask me what my favorite thing that I’ve worked on, and it’s a very difficult answer to give because I’ve met so many great friends on the projects that I’ve done, and I’ve loved everything that I have worked on. I only pick things that I’m very interested in doing. But I would have to say that LOST was probably one of my favorite things I’ve been a part of because last allowed me to just be me in terms of being an artist and a composer. I was able to write what I wanted to write and what I felt would be right for this show. Sometimes when you’re a composer or an actor you’re fitting into a box that’s sort of already created, and you kind of want to fit within this certain framework of something, especially when you’re working on big intellectual properties projects. It doesn’t mean there’s no freedom in doing something new. You can do something new, but you have that framework, wherewith LOST, there was no framework.

We had no spotting sessions for anything. They would just send me the episode and say, “Go!” That was really freeing, and no one questioned the style of music that I wanted to do or the emotional aspect I wanted to bring to it. It was just me doing what I hope was best for whatever was on screen in front of me. And, and it was really me showing you through my music how I was feeling while I was watching the show. I would write everything in order. I would never watch an episode on its own and then write the score. I would just watch it up to a point where I thought there should be music, and I would write music for that, then continue, then write for the next cue and then the next cue. That way I could be a part of the storytelling. I wouldn’t give things away that I might have given away subconsciously if I had watched the whole episode because it was a show that relied on surprise.

The other reason for no spotting sessions was that there was just no time. Everyone was struggling to get each episode finished. This was at a time we were doing twenty-four episodes a season, plus I was still working on Alias at the same time, so there was some overlap between the two shows. It was a real race just to finish things. I generally would have three to four days to write a score for an episode and record it and then you’re onto the next one. So it was a little nutty, but I loved it and I love having been a part of that show and have made so many great friends as a result of it.

We’d like to extend a special thank you to Michael Giacchino for taking the time to speak with us. His new album, Travelogue Volume 1, is available for purchase now. You can learn more about Michael Giacchino and his work, as well as links to purchase Travelogue Volume 1, on his website, michaelgiacchino.com.