Last week I worked on a big-budget shoot for a major film set for release as soon as October and as late as February of next year. The talent we were filming is one of the big ones, like household name big, trademark phrase big. Someone who would make worldwide headlines if they were to get sick. I’m bound by a pretty hefty Non-Disclosure Agreement to not reveal any actual details about the production itself, but one thing I can talk about is HOW we shot a major Hollywood celebrity during the COVID-19 era.

I got the call about this job about a month ago. It was the first time my phone has rung since March, when all production (more or less) stopped in California, and pretty much everywhere else. I was ecstatic at the prospects of getting off my couch, getting back to work, getting to play with my gear again, getting to see people and work with someone I’ve been a fan of since childhood.

The producer has been following the pandemic, and all of the various guidelines, studies, and companies that have sprouted up in response to the virus. It’s a lot, and not easy stuff, either, the kind of stuff you need an epidemiologist to really make sense of. And that is what happened, the production teamed up with a Ph.D. in Epidemiology and used them to guide the prep, and execution of the shoot.

There is so much to consider on a film set, especially one with an ambitious talent and budget, which comes with a large crew of random individuals, who all gather together in an enclosed space for hours on end, sometimes practically right on top of each other. The possibilities for passing the virus around are astounding. Fortunately, these people cared about everyone’s safety and took some extraordinary measures.

First things first, I had to get tested. I was sent to a private lab, where they had curbside brain stabbings, err, I mean Deep Sinus swabs. If you haven’t had one, it’s like sticking a pipe cleaner about 5 inches up your nose.* The test took only a minute, and off I went, teary-eyed and sniffling like I was in an onion factory. The results took about 36 hours to get, and came back negative, meaning I was cleared to work!

*DO NOT try sticking a pipe cleaner in your nose.

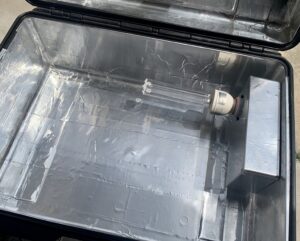

I have also been following the recommended procedures for disinfecting and as a production sound mixer, as I have some serious things to consider as well. I have microphones that go on boom poles that are swung above the talent. I also have wireless mics that get taped to the talent’s wardrobe, and transmitters that clip in their belt or sometimes get Velcroed around their ankle in a pouch. There are also wireless headphones that go out to many people on set. These all need to be disinfected, and so I built a box that has a UV-C light bulb in it made for disinfecting hospital rooms.

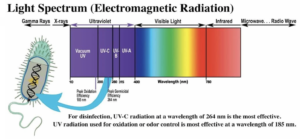

UV-C light is the lowest level of what is known as Ionizing Radiation, in the 200-300 nanometer range. What this means is that the wavelength of light that comes out is small enough to energize and destroy nucleic acids out of DNA strands in single-celled organisms. This is lethal to them and effective in killing just about any and all surface-dwelling virus, bacteria, and other such critters. This sounds kind of scary, but it is so low energy that it is not dangerous to use on a daily basis to disinfect objects. The box I built was a Pelican case in its former life, but now I can disinfect five wireless or five headsets at a time, and it only takes a minute. Speed is important after all, because nobody wants to wait for sound!

UV-C light is the lowest level of what is known as Ionizing Radiation, in the 200-300 nanometer range. What this means is that the wavelength of light that comes out is small enough to energize and destroy nucleic acids out of DNA strands in single-celled organisms. This is lethal to them and effective in killing just about any and all surface-dwelling virus, bacteria, and other such critters. This sounds kind of scary, but it is so low energy that it is not dangerous to use on a daily basis to disinfect objects. The box I built was a Pelican case in its former life, but now I can disinfect five wireless or five headsets at a time, and it only takes a minute. Speed is important after all, because nobody wants to wait for sound!

Besides this, I purchased a bunch of alcohol wipes, and a whole bunch of quart-sized ziplock bags, brand new tape rolls, non-latex gloves, a hat that doubles as a face mask, and I spent a whole day going over all of my gear, wiping down as much as I could. None of it has been out in public since last November, so I wasn’t that worried, but you still don’t wanna be “the source” when it comes to Covid. The day before we did our pre-lighting and rehearsal day, a truck picked up my gear and drove it to the studio. When it arrived, they have a Covid disinfecting crew, from Micron Disinfection spray everything with disinfecting spray. This company does all kinds of stuff including hospitals, Operating Rooms, “Trauma Cleaning” and is fully set up to deep clean anything. They had these Ultra Low Volume foggers that have disinfecting spray that evaporates after 10 minutes and leaves no residue. Everything gets disinfected before it goes in the studio, cameras, lights, props, everything but people. Once my gear was disinfected, it was to remain on the stage throughout the shoot. They also had Covid managers walking around making sure everyone adheres to the PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) protocol, Distancing, and would have alcohol spray for anyone who should want it.

When it comes time to shoot, we had protocols to follow. First, there are zones. People who are in the office, out making runs and other jobs that never go on set are green zoned. They need to follow basic things like mask-wearing and regular hand washing and are not allowed on set. Outside the stage is Green Zone. Everyone who needs to be on set, but not in direct or close contact with the talent is Yellow Zoned. We need to get tested every four days and need to follow the onset protocols, including not going within 27 feet of the talent without a face mask and face shield in place. The Red Zone people get tested every other day, and must wear the mask and shield any time talent is on set. Anyone who needs to come in direct contact with the talent must wear paper gowns and gloves. This includes Hair, Makeup, Wardrobe, and Sound. The rest have the face masks and shields all the time.

The talent has a trailer, outside where they would go isolate whenever we were redoing scenery or lighting, rehearsing movements, and stuff like that. A stand-in was used during all of the setup and rehearsal, and it was shown to the talent before we started filming. Every two hours we would stop working, open the stage doors, turn on the air circulator, and leave the stage for 15 minutes while the Covid team re-hazed the entire stage. We could at these times take our masks off, as long as we stayed distant from each other, and get some snacks at the Craft Service tent.

Crafty, as it’s called, has a variety of snacks for the crew to keep us hydrated and on top of our game over the sometimes long, sometimes tough workdays. On this occasion, it was pretty easy work, but we were in a heatwave in southern California, so cold drinks were going like gangbusters. Usually, Crafty is a mix of being served things, and a grab and go type of setup, but not now. Everyone had to line up six feet apart and wait your turn, pick out what you wanted and have it handed to you. The same went for lunch, where we all had to line up. There was a whiteboard with menu items and we would pick out whatever.

These items were put in those styrofoam to-go containers, wrapped up plastic ware, and when we sit down to eat, there was an entire stage lined with plastic tables, 8 feet apart, with 2 seats each at the long ends.

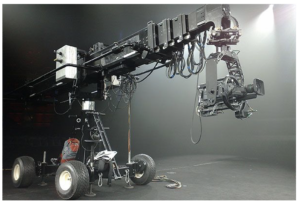

Back on set, the camera department employed a Technocrane™, which can extend and retract the camera to get the shots they want without having to be so close. Lighting was largely set up ahead of time to reduce the number of hands on set. When grips and electricians do come in it’s in Yellow mode, when Talent is offset. When we “Go Red” that means they need to clear out before talent lands. Walkie talkie use is pretty common on film sets, but it comes in handy now to communicate at a distance. One thing became clear wearing masks all day is uncomfortable. They pull at your ears, humidity builds up giving you a sweaty goatee. There are these spacer things however that take the strain off and make it easier. The breaks we took were sweet respite, and you could wipe your face off, and start again. It was uncomfortable but hardly undoable.

The prospect of going back to work in the film industry is daunting, challenging, expensive, time-consuming, and adds multiple layers of difficulty, risk and liability into an already haphazard process fraught with unforeseen disasters. To the people who are willing to be diligent, and smart about it, it IS doable, and while it will certainly affect the bottom line, there is still money to be made, because people need entertainment now more than ever. I believe we will find it to be an acceptable expense and a manageable risk.

Thomas Curley, CAS is an Academy Award and BAFTA winning Sound Engineer and is the cohost of the Film Dorks Podcast, presented by Screen Radar.