There are films that change the way you think about life, others about the world, and then there are films that make you think differently about the art of cinema itself. Rarely do we find films that do all three. Darius Marder‘s feature film directorial debut Sound of Metal is one of those films where we do. It taps into the human spirit while forcing us to reinterpret every aspect of it. Similar to when you put on headphones to listen to music and suddenly hear notes and attributes that you never heard before; Sound of Metal invokes an intricate auditory experience that challenges, enlightens, inspires.

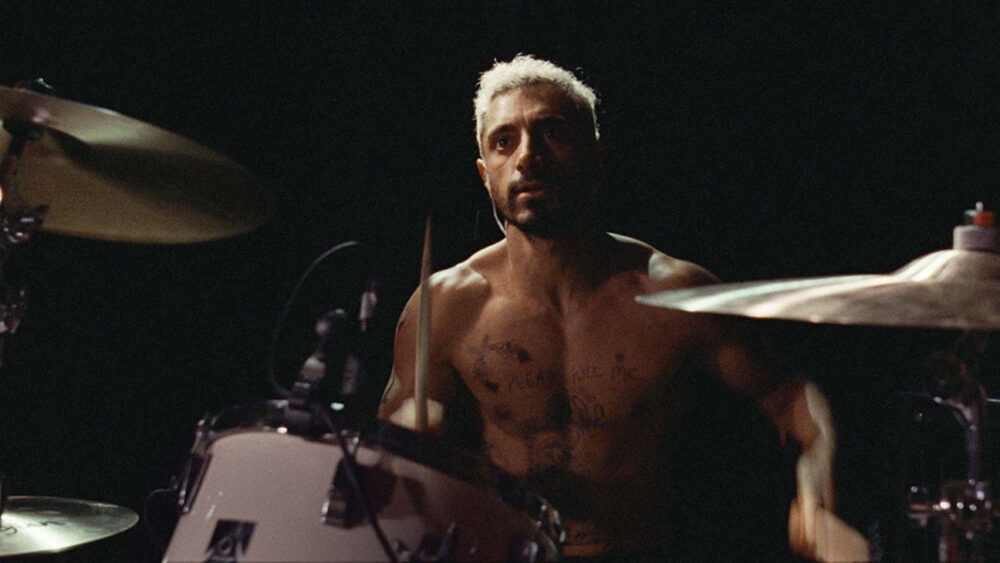

The film opens loudly with Ruben (Riz Amhed – The Night Of), the drummer for a metal band called Blackgammon, doing what he does best, delivering a flurry of beats to accompany the driving vocals of Lou (Olivia Cooke). They perform an earsplitting, angsty style of music which from many peoples’ perspectives could easily be dismissed as noise, but to them and their fans its’ art. In this film, it is often all about perspective.

The pair are not only musical partners they are also dating, and traveling the country in their RV – a mobile dream machine packed with recording equipment and memories. It serves as a refuge that can literally be used to move on from the pain of their pasts. The anguish is physically represented on their bodies in the form of self-cutting scars and menacing tattoos. We watch as they sleep, dance, and have those little mundane conversations we all take for granted. You get the sense that as long as they have their music and each other to lean on, life is good. The bliss is replaced with fear when, for reasons unknown, Ruben’s hearing is suddenly off. Voices and sounds that should be crystal clear instead sound muffled and distorted, quickly deteriorating. It is terrifying to witness and we do so first hand.

A visit with an ear specialist transforms into a high-tension situation. What unfolds is a simple yet relentless scene. For anyone who has had the misfortune of being delivered a bad medical diagnosis, this scene will certainly be distressing. Marder’s approach elevates these moments, making the prognosis feel as it is ours, the viewer. To drive home the anxiety, we are not only in the room but often trapped in Ruben’s head as he learns his fate. Betrayed by our own senses. Through the use of sound, there is suddenly a barrier preventing us from communicating properly. The sound or voices are being produced but we cannot distinguish what is being said. It is terrifyingly effective.

Marder and co-writer brother Abraham Marder avoid the expected melodramatic pitfalls by not taking the conventional route. Instead, they take us on a more personal, internalized journey. While an undeniable present throughout, it is at this point where Nicolas Becker‘s sound design really grabbed hold of me and didn’t let go. We experience Ruben’s auditory challenges in an inventive way that is neither gimmicky nor overused.

For Ruben this is not just about hearing though, it is the loss of identity and control. Without the ability to hear he sees his relationships with Lou as a bandmate and a lover, and the music itself is at risk. The only way he sees to regain this control, to become “normal” again, is through an expensive cochlear implant surgery (a small electronic device that electrically stimulates the cochlear nerve to restore some hearing).

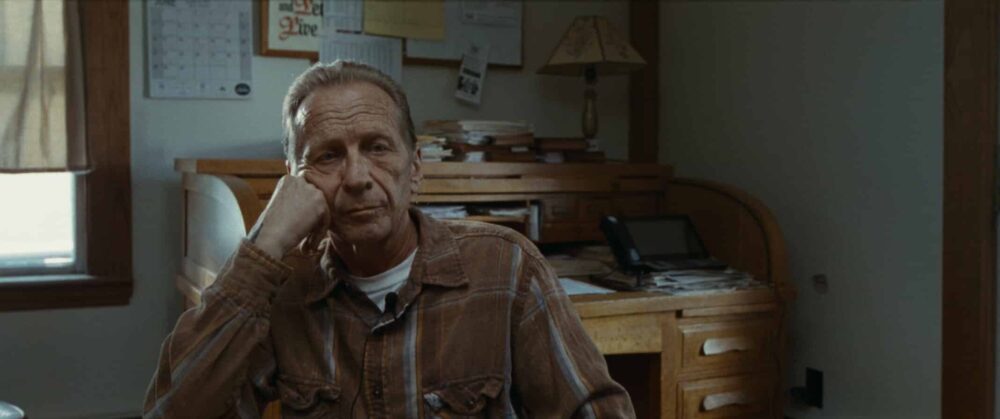

Out of fear that Ruben will slip into some bad habits, Lou enrolls Ruben into a deaf community home, shifting the film focus from their story to one about his self-discovery, hope, and healing. Here, Joe (Paul Raci), the tough loving but fair man who runs the community reminds Ruben (and us) an important lesson. Deafness is not a disability and if he wants to move forward in his life he will need to take that to heart. It is not his hearing he needs to fix, but rather his view of the world.

The film’s use of sound is not only groundbreaking, it’s often poetic. Marder takes advantage of all his instruments to orchestrate a riveting audio encounter that allows us to experience hearing impairment first hand. Abstract sounds, a cacophony of distortion, silence, and even subtitles are expertly combined, evolving throughout into a complex exploration of deafness as never experienced before. The most surprising aspect is that it transfixes to the point you may not even realize what is happening.

Honestly, the use of subtitles threw me at first. I wondered whether I accidentally turned them on at some point. Then they disappeared from the screen at a time when I needed them the most – when I needed them to help clarify what I was hearing. That is when it all came together: a cinematic epiphany. It is as if Marder (and his team) were able to decode the enigma of hearing impairment in a way that also amplified the film’s message allowing it to transcend beyond the usual limitations of storytelling. Through the use of shifting sound perspectives, the film will open eyes and help shed some unfortunate notions about deaf life being empty or incomplete. In fact, it is quite the opposite – a vibrant world teeming with life, emotion, and spirit.

One particularly effective scene, has Ruben sitting in a circle meeting where everyone else is in a conversation using sign language. At first, we see it from Ruben’s point of view, who does not know how to sign. All we hear is silence. Then the perspective shifts outside his head to reveal that the conversation is actually lively, animated, and loud. I fear my words do not do justice to just how wonderfully nuanced the use of sound is here.

The film balances on the incredibly powerful performance of Riz Ahmed (who learned ASL and drumming just for the part – whoa!). While Ruben is not always the most likable character, it is still hard not to root for him. This is a testament to Ahmed who creates a real tenderness behind the character’s often rough exterior. His expressive eyes are a passage to the heart of a character battling inner fears and doubts. This is most evident in scenes between Ahmed and both Cooke and Raci where he has to interact with those who most want to help him. Both do tremendous work here – often delivering the most impact in the quieter moments between the lines of dialogue.

The film bounces back and forth between well-placed louder and quiet moments. That is why it’s surprising that one of the most powerful moments for me was a familiar sound – a single laugh. It seems simple, but during a film that puts the audience through a lot, it was a sign of hope to cling to.

Sound of Metal combines impeccable, innovative sound design and a riveting performance by Riz Amhed to deliver one of the most compelling films of the year – a visceral journey. It will resonate within you long after viewing.

Quick Scan:

Sound of Metal combines impeccable sound design and a riveting performance by Riz Amhed to deliver one of the most compelling films of the year.