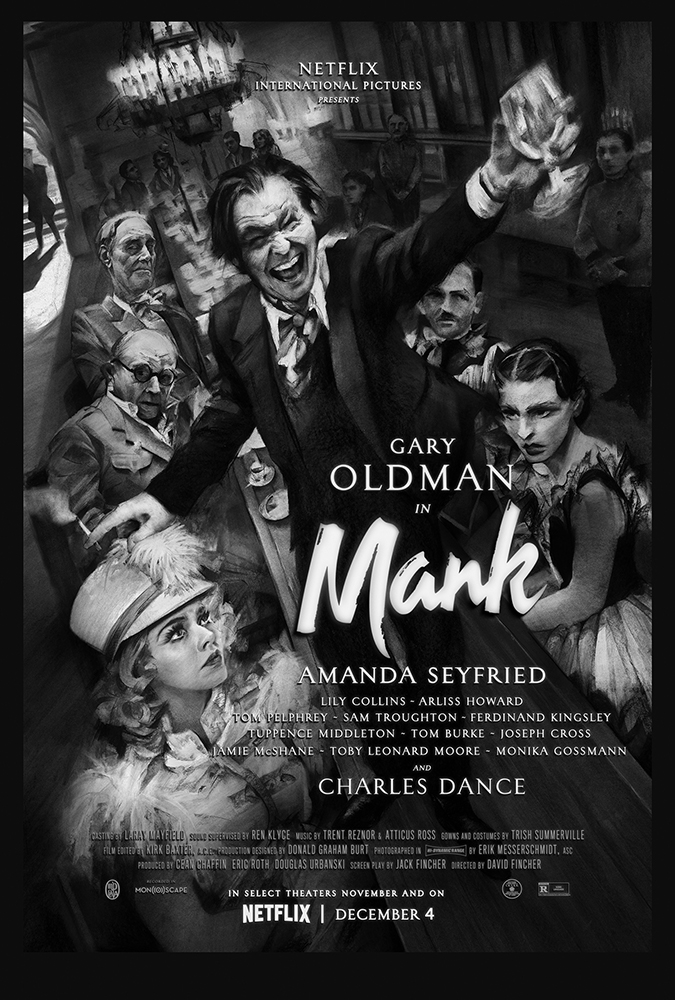

Welcome to 1930’s Hollywood – a bygone era where the rooms are smokier, the drinks were harder… and no one insults their mother. Mank, David Fincher‘s first film in six years, is unlike anything he has directed before. The meta-biopic transports us back in time to tell the story of Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), a self-destructive man taking his shot at redemption while simultaneously writing an arresting love letter to the cinema of the 30s. Fincher takes us on a celluloid time machine trip back to a world that no longer exists and actually may never have… part reality, part nostalgia, part legend. It is also an exercise in technical precision, snappy dialogue, bouncy score, and shot in glorious, high contrast black and white. One thing it is not is a history lesson.

Written by Fincher’s father, Jack Fincher, the banter-filled screenplay tells the story of Mankiewicz (aka Mank) a talented but seemingly washed-up writer who plays head games with the demons that threaten to devour his humanity. Just as it looks like he has reached a low point in his life and career, Mank is approached by 24-year-old Orson Welles (Tom Burke) to write what is now considered the greatest film of all time, Citizen Kane.

Welles’ film, Citizen Kane, is a thinly-veiled account of the life of one of the richest, most powerful men in the world, William Randolph Hearst (the regal and restrained Charles Dance). Fincher’s script dabbles in the folklore behind who deserves credit for the writing of the film, but is more interested in the man whose alcoholic ways, sharp tongue, and disarming charm often make him the least predictable yet wittiest man in the room. There isn’t a conversation that he won’t punch up or at least add some friction.

One complaint some audiences will certainly have is the film can feel meandering at times – there is a lack of a strong, easy to consume narrative. Mank is a little more challenging, bouncing back and forth from 1940, where a bed-ridden Mankiewicz is writing the Kane screenplay, to flashbacks of the 30s that show some of the moments and people who influenced the script itself. There are few “big moments” here. Instead, there is a lot of mood on display.

This film is determined to keep us under its spell, locking us into the 30s/40s Hollywood setting as Mank guides us on a loose tour. We weave through to movie sets, Hollywood backrooms, and the studio offices of the Hollywood elite like Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and allured by Hearst’s mistress Marion Davies, Amanda Seyfried. The scope of the film extends beyond the life of a troubled screenwriter to cover the political and social aspects of the time. Propaganda, anti-socialist, The Depression all work their way onto the canvas to paint a picture of the time. Even though it is set almost a century ago, much of which will speak to today’s audience.

Those with a keen eye and working knowledge of Citizen Kane will recognize moments in Mank’s life echo and may have inspired the screenplay. Luckily, Fincher shows restraint; he avoids leaning on a Forrest-Gump-changes-history type novelty act. Most of these Kane-inspiring references are subtle winks to the camera for fans of the Welles’ film. Those who have a soft spot for old Hollywood will instantly be enamored by the attention to detail Fincher displays, capturing the tempo and feel of a film of that era. That is what hooked me; a modern biopic, shot in the style as if produced at the time of the characters, where the characters talk, move, and match the mannerisms of films from the era, even if it probably was not how people actually spoke.

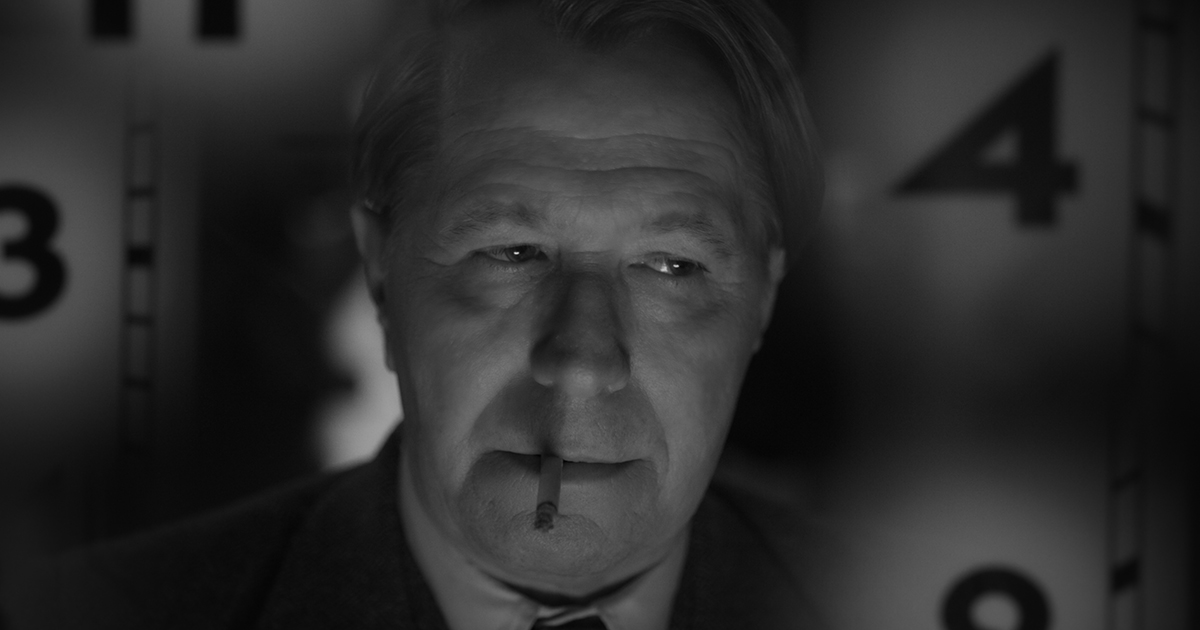

The film is an unparalleled technical achievement, a masterclass on cinematography by Erik Messerschmidt. If you were to walk into Mank not knowing when it was shot you would swear it was produced eighty-plus years ago. He uses deep focus and meticulous lighting techniques to recreate the Kane-esque film stock look even though it was shot completely on state-of-the-art digital. Everything on the screen feels sharp, textured, and contrasty. Fincher includes everything from side-to-side film wobbles, vintage title cards, fade-outs, wipes, and even cigarette burns (a cue to projectionist to be ready to switch film reels). Kirk Baxter‘s editing adds a trance-like cadence that injects an artful touch to every cut and transition. While the film pays respect to 30’s and 40s cinema it never crosses over into gimmickry.

Trying to find a flaw in the production design may end up fruitless. Trish Summerville‘s costume designs are entrancing – so spot on you would almost think they were perfectly preserved originals stolen from the warehouse of an old Hollywood studio. Oldman’s Mank often looks disheveled and rumpled while Seyfried’s Marion sparkles and shimmers draped in Old Hollywood glamour. The precision continues with the score, another collaboration between Fincher and the team of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (The Social Network, Watchman) goes from snappy with horns a blazing to menacing and solemn – a pitch-perfect complement for the time period. The film feels like a shoo-in for at least a handful of technical Oscar noms.

The praise should not end there. The acting is tremendous and never breaks the illusion. The ripped from the classics dialogue delivery tiptoes the line, but never slips into caricature especially when combined with the spot-on body language and mannerisms. You could edit these performances into a classic film and no one would bat an eye.

Gary Oldman disappears in the role of Mank; his performance feels natural and absolutely seamless; a mixed bag of charming, flawed, precarious, and bold – a complex performance made to look easy by Oldman. Seyfried breathes depth into Marion making her so much more than just a pretty face – she is layered and hypnotizing. She shares some of the films’ most magical moments with Oldman. His softer side peaks through the tousled exterior in a peculiar yet endearing friendship. On the other end of the spectrum is Arliss Howard as Louis B. Mayer, who steals scenes with his smarmy and manipulative demeanor; a character worthy of a film of his own. Lilly Collins, Tom Pelphrey, Joseph Cross, and Ferdinand Kingsley are just a few members of the vast ensemble who deliver some impressive performances.

I was hypnotized by Fincher’s vision – his ability to recreate the familiar feel of films from that era – cinematic comfort food. I loved just taking in all the sights and sound of his filmmaking on display here – from the set design to the performances and everything in between. Technically, it is near genius. While the non-linear storytelling can feel scattered and aimless at times, patience prevails with a satisfying nuanced story of a man teetering on self-irreverence. Those expecting big movie moments may feel left in the cold. This is not a foot race, but more of a leisurely, captivating walk through old Hollywood. Cinephiles will find it an embracing throwback to the films we have watched, rewatched, studied, and loved.

My recommendation, try do not to go into the film with exceptions (if possible). Forget it is Fincher, forget the connections to Orson Welles and Citizen Kane, forget the faces of the actors you recognize. Just take it in for what it is. It may be a lot to ask, but it makes for a hell of an experience.

Mank is streaming exclusively on Netflix.

Quick Scan:

The story is a meandering stroll, that rewards with absorbing performances and technical mastery that will transport cinephiles right into a long-gone Hollywood era.